Henderson: Making sense of negative yields

Currently there is $13 trillion of negative yielding debt around the globe as falling developed market government bond yields are pulling down yields on global bonds in general. So why is there demand for negative yielding assets, will the trend continue and how long can bonds remain attractive against this backdrop?

06.09.2016 | 10:41 Uhr

Negative yields — the origins

Low yields, in normal times, are the bond market’s signal of economic slowdown with investors moving into safer haven assets and accepting lower yields as a result. But the current historically low yields in a number of developed countries are not a signal of impending recessions, rather the result of years of ultra-loose monetary policies.

Negative yields on government bonds have become more widespread over the past couple of years, primarily as a result of central banks moving interest rates into negative territory, in an attempt to deliver greater monetary policy stimulus into the economy. In addition, continuing quantitative easing (QE) programmes (bond purchases) by major central banks have worked in concert with these negative short term rates to push bond yields further into negative territory. This is because the central bank purchases create additional demand for government bonds at a time when net government bond issuance (new supply each year) is actually declining.

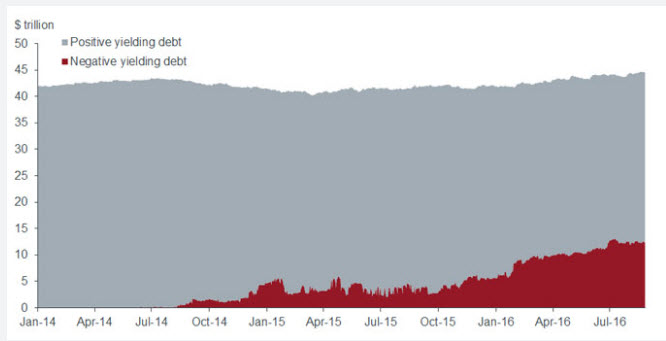

As the chart below shows, negative yielding issues are becoming increasingly prevalent.

Chart 1: Global negative-yielding debt volumes rising Source: BofA Merrill Lynch, as at 26 August 2016

Negative yields — the basics

Given that the price of a bond moves in the opposite direction to its yield, it follows that the lower the yield on a bond, the higher its price. In the case of a negative yield, this means that the price paid by the investor will be more than the total of the face value plus coupons that he or she would receive should the bond be held to maturity. In this scenario buying and holding a negative yielding bond to maturity would result in a guaranteed loss.

Why buy bonds with negative yields?

There are a number of valid reasons that investors seek to invest in negative yielding bonds. These include concerns over the future direction of an economy and a subsequent ‘flight to safety’ by investors, fears over deflation, mandate or regulatory requirements. In the first two cases a small loss on an investment could be acceptable if one is concerned more with the actual return ‘of’ money or capital, be it at a slight loss, rather than making gains ‘on’ that money. To pay a price over the face value could be viewed as an insurance premium on receiving the capital back at a given point in time.

Investors have bought negative yielding government bonds for other reasons too, such as in an attempt to avoid paying a greater negative interest rate on their deposits at banks. In addition, some investors are speculating on whether interest rates could be cut even further in places like Europe and Japan, leading to further declines in government bond yields, thus higher prices and capital gains. This is known by some as the ‘greater fool theory’ which implies there will always be a buyer at an even lower yield. Other investors in negative yielding bonds are doing so as part of a currency strategy hoping to make big currency gains, which would more than offset the negative yields.

Some institutional investors are constrained by mandates; banks, pension funds and insurance companies have to invest in government bonds regardless of the returns on offer. Banks, for example, are required to invest in liquid assets such as government bonds. Insurance companies need to hold government bonds as part of their reserves and pension funds employing liability driven investment (LDI) strategies need to hold government bonds to provide the cash flows needed to match their future liabilities. Negative yields – a gathering trend?

Germany issued its first negative yielding 10-year sovereign bond in mid July 2016. Although 10-year bunds were trading with negative yields in the secondary market in the few weeks prior to the new issue, this was a symbolic moment given that the 10-year bund is considered the benchmark issue in Europe. Additionally, just prior to this issue, Germany’s railway operator Deutsche Bahn became the first non-financial company to sell a corporate bond with a negative yield in euros.

Government bond yields are likely to remain negative as long as interest rates remain negative in their respective countries, especially bond issues with a shorter maturity. Many central banks, including the Bank of England, have expressed some concerns over taking interest rates negative, given the damaging impact it may have on bank profitability, and this may stop negative yields on government bonds becoming more widespread.

However, there are increasing question marks over the effectiveness of current monetary policies, particularly when deployed in unconventional forms like QE. Should attempts to deliver monetary policy via other methods fail, negative interest rates may well be the only option available.

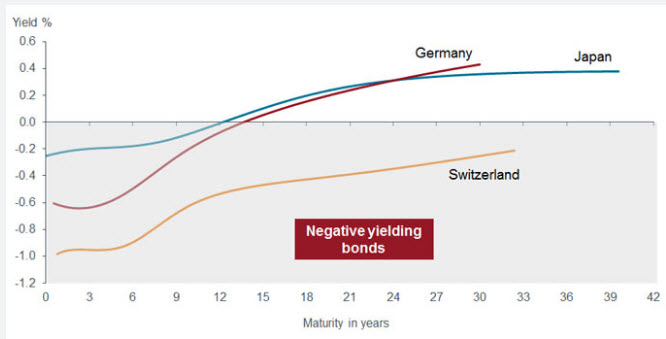

As can be seen in the chart below, Swiss sovereign bonds are currently trading with negative yields in all maturities up to 30 years and over, while German and Japanese sovereign bonds have negative yields to slightly over 10 years.

Chart 2: Sovereign yield curves with negative yields (simple yield, %)

Source: Barclays, as at 29 August 2016

Will negative yields become widespread in the UK?

Some UK government bonds did briefly trade with a negative yield in the days after the European Union (EU) referendum. The Bank of England cut rates in early August to 0.25% (or 25 basis points) but more recent comments suggest it is keen to keep them at marginally positive levels for now. Should interest rates be cut further to around 5 or 10 basis points, we may see some short-dated government bonds trade with a negative yield. However, for negative yields to become more widespread across the maturity spectrum, the Bank of England would need to take rates into negative territory.

Why are their concerns around the profitability of banks?

Whereas previously economic theory assumed 0% was the lowest level interest rates would reach, that has now proven not to be the case, as at marginally negative interest rates, most market participants are unlikely to store large amounts of non-interest bearing instruments like notes and coins, rather they will keep money in its interest-bearing electronic form.

The banking system has managed to adapt to negative interest rates, though there are increasing concerns on the impact of these rates on the profitability of banks. If the costs of negative rates were to be borne by banks, it would put serious pressure on their profit margins (net interest margin, the difference between their lending and deposit rates). With the ability to make money impaired, banks could choose to lend even less into the economy. Additionally, sub-zero rates could even move them to take on greater risks in search of profits. Neither of these scenarios would be considered good for economic stability generally.

What next for government bonds?

With government bond yields of all maturities having declined in the UK, particularly since the EU referendum, holders of these bonds will have seen substantial gains. Given the current low yields on government bonds, we are unlikely to see significant further declines, especially if interest rates stay positive as the Bank of England has suggested.

The banking system has managed to adapt to negative interest rates, though there are increasing concerns on the impact of these rates on the profitability of banks. If the costs of negative rates were to be borne by banks, it would put serious pressure on their profit margins (net interest margin, the difference between their lending and deposit rates). With the ability to make money impaired, banks could choose to lend even less into the economy. Additionally, sub-zero rates could even move them to take on greater risks in search of profits. Neither of these scenarios would be considered good for economic stability generally.

It is worth considering how much longer this scenario will continue and, should central banks begin to tighten monetary policy, the pressure that will be placed on all asset classes. Investors need to monitor developments closely and potentially reassess how they will best meet their investment goals and future liabilities. Adopting a diversified approach may prove the best way to adapt to this ‘new normal’ with expectations of future returns reset accordingly.

Diesen Beitrag teilen: