NN IP: Nothing to fear but fear Itself

Risk has always been around and probably always will be. With this in mind, we can say that investors are not overly complacent (yet), despite the low levels of volatility in equity and bond markets.

18.05.2017 | 14:09 Uhr

It’s funny how the mind works. First we fear secular stagnation, then we worry about central banks tightening policy. First we fear lack of productivity growth, then we worry about job destruction from technological disruption. First we fear political shocks impacting markets, then we worry about the lack of market volatility. It is almost as if we always want to be worried about something. If the market is already in turmoil, we always have the illuminating benefit of hindsight to explain why this is. Even worse, the reasons we use often help to build the fear that the problems will last.

On top of that, calmness in markets also seems to spook people. They perceive the calm as investor complacency. And if they overlook the risk, they see the likelihood of problems around the corner only rising. And even if that likelihood is rising, it seems equally feasible that a lingering crisis-trauma in our minds is continuously making us ask ourselves: “Why not worry?” And once we start looking, it’s not hard to find a reason to worry, especially if Situation A (one of high volatility and a lack of productivity growth) and the inverse of Situation A (one of low volatility and technological “disruption”) are both perceived as reasons for concern.

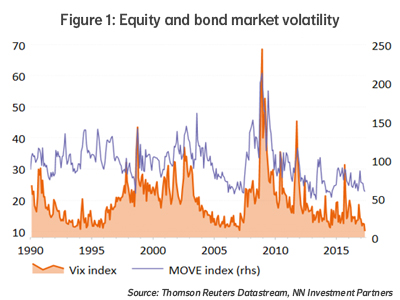

The hot topic of the day is the record-low level of expected volatility in the US equity market as embedded in the option market, and as expressed by the well-known VIX index. Meanwhile, the expected volatility of the US bond market, measured by the MOVE index, has also drifted to the lower end of its 30-year range (see Figure 1). These are interesting observations, but before drawing conclusions from them, global investors need to balance them with other metrics that describe investors’ risk appetite and behaviour. What stands out then is that the positioning of investors is still not very aggressive. Cash levels remain above long-term averages. Exposure to both bond and equity risk in active investor portfolios is not aggressive, either, and the risk premiums that investors demand in capital markets are mostly at or above average.

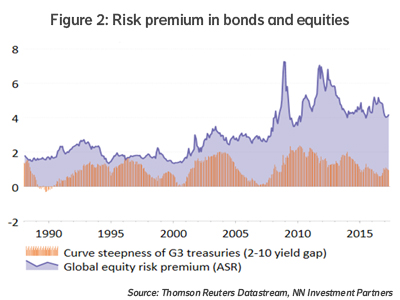

Figure 2 shows that global equities still offer an relatively attractive premium compared to government bonds, while bonds themselves roughly offer an average compensation for risk compared to cash. So neither of the core assets in financial markets seems to reflect complacency about the uncertainty that the future always offers to investors.

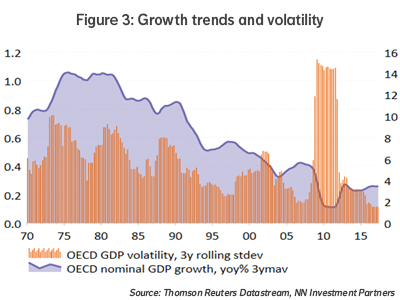

Still, one could argue that the compensation offered is not enough for the remarkably uncertain future of this time. And one could be proven right. However, it is actually much harder to prove this point than it might look at first, given the behaviour of the underlying economy or the policy and political backdrop. On many metrics the current economic and profit recovery is the strongest and most robust we have seen in at least a decade. Moreover, the behaviour of the economy has been remarkably stable is recent years (see Figure 3). Therefore, both the direction of change and the observed volatility in the underlying fundamentals give limited support to the view that markets are mispricing fundamental risks.

On the policy and political front there are more than enough potential risk factors – US tax reform US, tightening of monetary policy, the Italian election, or conflict in the Middle East or with North-Korea, just to name a few – but an honest perspective on the past shows that these types of risk are around most of the time. Brexit, the Euro crisis, the invasion of Crimea by Russia, the fiscal cliff in the US and the Lehman collapse may be most fresh in people’s minds, but similar events in previous decades either happened or came close enough to happening to spook investors. The 9-11 terror attacks, the US invasion(s) of Iraq, the Asia/Russia/LTCM crisis and the collapse of communism in the Eastern Europe are just a few examples of the shocks that happened in the 1990s and early 2000s. This does not prove that future policy or political events will not move the market down substantially, but it does suggest that the market is no more complacent than average about such probabilities.

As always it therefore remains crucial to stay on guard and to respond quickly to a shift in market behaviour if need be. But there is actually a good reason not to worry too much. Investors pay a significant cost for worrying too much. This cost is called “opportunity loss”. Many of the reasons for caution available today (and some even better ones!) were available in recent years. The investors who were guided by fear in those years might not actually have lost money, but have certainly “lost” the opportunity to do substantially better for themselves or for their clients. In a world where investment returns are harder than ever to find, the reluctance to exploit opportunity can grow to become a bigger investment problem than most of the current fear factors can ever create on their own. For investors, the only thing to really fear is fear itself.

Diesen Beitrag teilen: