UBS: Central banks on the hunt for a medicine

Having explored almost all other options, markets are now speculating that monetisation could be the next step. Monetisation can look like a free lunch when interest rates are stuck at zero. But economics teaches us that there is no such thing as a free lunch, so who would end up picking up the bill?

03.05.2016 | 15:59 Uhr

Central banks have been searching for new medicines to help ailing economies, but some of the treatments could have unpleasant side effects. One of the most radical, and possibly most effective, policies is monetisation, known popularly as helicopter money (see Print prescription, 26 April 2016). Monetisation seems to be an easy way to raise inflation expectations, which is useful if expectations have fallen below target. But economics teaches us that there is no such thingas a free lunch, so who picks up the bill?

Unsurprisingly it is central banks, which might explain why central banks are not so keen on monetisation. In a world where interest rates are already at (or below) zero, the problems from monetisation may not be so apparent. So fast forward to some point in the future when inflation is high and the central banks need to raise interest rates.

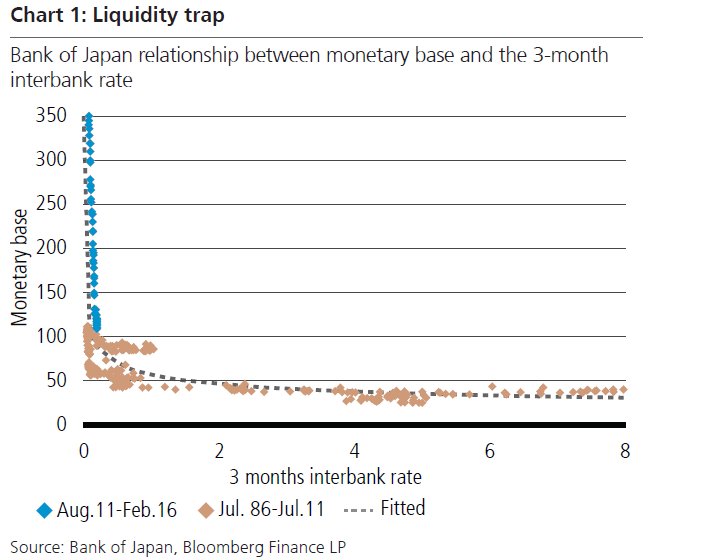

In a market you can control either quantity or price, but never both. Central banks had been controlling the quantity of the monetary base (through monetisation), but now need to target the price of money (the interest rate). Traditionally, they would decide on the interest rate and then their open market operations team would inject or remove enough liquidity to move the interest rate. To get interest rates higher, a central bank removes liquidity to make money more scarce, and hence more expensive (chart 1). Injecting liquidity pushes interest rates lower.

There is a lower limit to interest rates around zero. A situation where the central bank can increase liquidity but have no effect on interest rates is known as a liquidity trap. The trap is not complete: extra liquidity will still affect longer term interest rates or the price of other assets. But the effectiveness of monetary policy is still severely curtailed.

In a liquidity trap it does not really matter if the liquidity injection came from quantitative easing (QE) or monetisation. But it does matter once you try to reverse the liquidity so as to raise interest rates.

With QE, the bank injected liquidity by creating money to buy assets. So removing liquidity is easy, just do QE in reverse. Sell the asset and then destroy the cash that you get for it. With monetisation the bank injects liquidity by giving it to the government (or directly to households), but does not receive any assets in return. That means there is nothing to sell to soak up the extra cash.

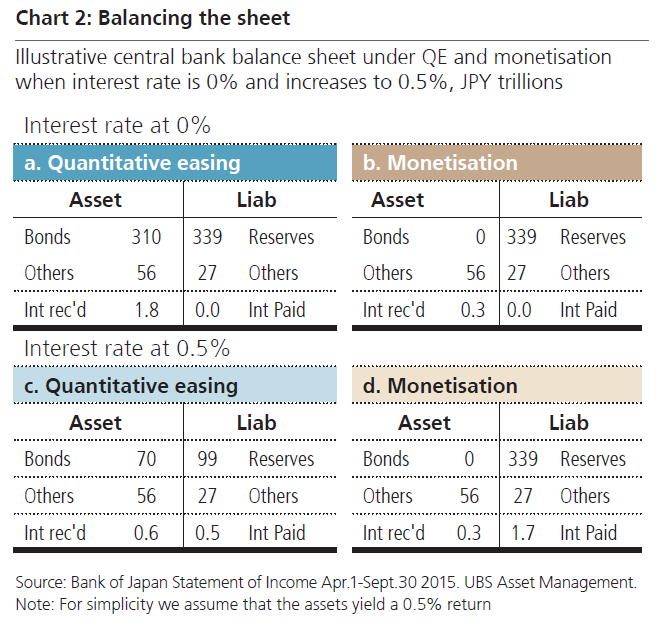

The difference is nicely illustrated by comparing how the central bank's balance sheet would look if it raised rates following QE, versus the same increase following monetisation. To make it more realistic, we base the illustration loosely on a simplifiedversion of the Bank of Japan (BOJ) balance sheet (chart 2).We will call this imaginary institution the Central Bank of Japan (CBJ).

So far the imaginary CBJ has bought over JPY 300 trillion ofJapanese government bonds, which makes up almost all of theasset side of its balance sheet. This was paid for by creatingbank reserves (which are electronic cash). With a zero depositrate, the CBJ does not pay any interest to banks for the reservesthat they keep at the CBJ. The bonds do pay interest, averagingabout 0.5%. So the CBJ is making a decent profit (chart 2a),although from this it has to pay for its own operating expenses.

Suppose instead the CBJ monetised the government debt bysimply writing off that debt. The government would need torespond by increasing their spending to have an economicimpact (as set out in our previous Economist Insights), but that isnot important for the balance sheet. Once the bonds have beenwritten off, there is no longer any revenue. The CBJ still makes aprofit because they do not have to pay any interest, and there isa little income from other assets on the balance sheet (chart 2b).But it is far less than under QE, and the CBJ has negative equity(liabilities exceed assets). Nobody is going to be too worriedabout negative equity as long as the CBJ is still making a profit.

Now suppose the CBJ wants to raise interest rates to 0.5%.The first step would be to increase the deposit rate, so thatreserves are now paid 0.5%. This would provide a floor to theinterest rate because no bank wants to lend to another bankfor less than they could get by leaving cash at the CBJ.Under QE, to get the interbank market to match 0.5%, theCBJ would need to soak up about JPY 240 trillion of liquidity.Ignoring for the moment the shock that would cause to thegovernment bond market, this would shrink both bonds andreserves by the same amount (chart 2c). Revenues would fall,but so would liabilities. The fall in liabilities is useful becausenow the CBJ has to pay interest. Overall the CBJ is still makinga profit, albeit a much smaller profit than before.

If the CBJ had monetised, then the only mechanism they havefor raising interest rates is by raising the deposit rate. There isstill plenty of extra liquidity floating around the system, so theinterbank market is likely to be behaving very strangely. Butcrucially, interest received is unchanged although now interestmust be paid on a huge level of reserves (chart 2d). Notonly does the CBJ now have negative equity, but it also hasnegative interest income. This is much more worrying.

Inequitable

Big deal, you might say, why doesn't the CBJ does print moremoney to make up for its loss? Effectively, the CBJ would bemonetising its own liabilities. Unfortunately, creating cashultimately means creating reserves, and interest would have tobe paid on those reserves. That means a bigger income holethat has to be plugged. It is easy to see this spiralling out ofcontrol: printing money to balance the books, only to find thatthis creates an ever bigger need to print more money. Nextthing you know the central bank has lost control of the moneysupply. Hyperinflation, here we come.

The next option is for the government to come to the rescue.This seems only fair, given that the CBJ had just written off mostof the government's debt. One way to do this is to plug theincome gap, and give the CBJ enough money to balance out theloss on interest. This means higher taxes, (yet another blurring ofthe distinction between fiscal and monetary policy). And it wouldalso mean the central bank was no longer really independent ofthe government.

The second approach would be to recapitalise the bank's balancesheet. The government would issue debt and place it on the bank'sbalance sheet. But this has effectively reversed the monetisation,turning it into a temporary measure. And from an economicperspective, a temporary monetisation is indistinguishable from QE– although it may have encouraged a fiscal stimulus at the time.

Arguably the CBJ should not be considered insolvent because inthe future it can be expected to earn income from creating money.The net present value of this future stream of seignorage, as it iscalled, could arguably offset the losses, as long as the losses arenot too large. But again this blurs the line with fiscal policy – ifthe seignorage revenues are going to the CBJ rather than thegovernment, there will be a budget shortfall that requires revenueto be raised.

No doubt there could be some innovations to circumvent someof these effects. For example, maybe the CBJ could only raise thedeposit rate on marginal changes in reserves rather than all reserves.(much as he BOJ recently announced with negative deposit rates).Or make 100% of the reserves mandatory so that banks can'teffectively re-use them. But there are still no free lunches; it wouldsimply mean that commercial banks pick up the tab.

As with any medicine, dosage in monetary policy is important.The level of monetisation in the example above wouldalmost certainly be an overdose that would send inflationexpectations spiralling. A smaller injection of monetisationwould produce commensurately smaller side effects.

Den vollständigen Bericht lesen Sie hier.

Diesen Beitrag teilen: