UBS: Profit motivation

The function of profits used to be so simple. In part they were used to reward investors short-term, via dividend pay-outs, but in the main they supported capital expenditure to grow the business. Not so today: the incentives driving firms and their CEOs are rather different.

19.04.2016 | 11:15 Uhr

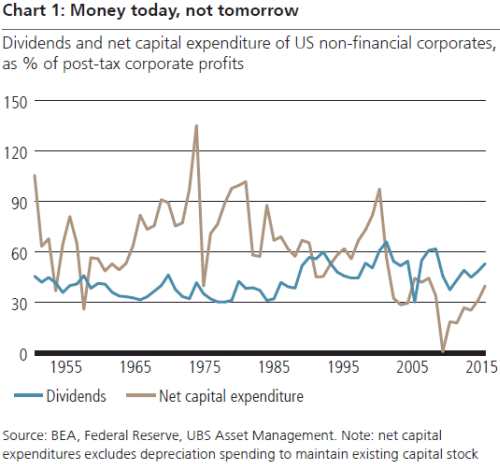

Everyone knows that firms are driven by the profit motive, but what do firms do with profits once they get them? In the simple textbook view of corporate finance, firms divided their profits between dividend payouts and capital expenditure (capex) to expand the business. If there was insufficient cash then they would borrow to finance their expansion. To be fair, this was a pretty good description of how firms behaved in the 1950s through to the 1970s. Throughout these three decades, about a quarter of corporate profits were paid out in dividends (chart 1). The remaining three-quarters went to capex, sometimes supplemented by a net increase in borrowing.

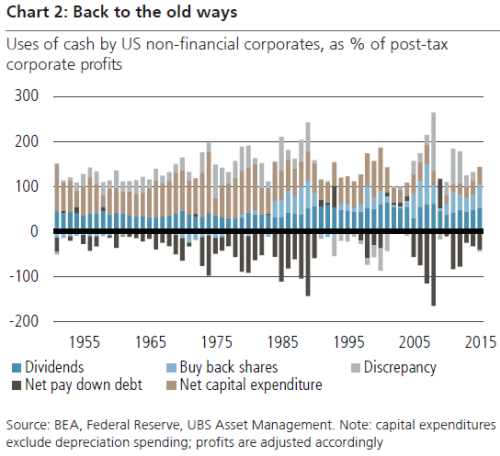

Then in the 1980s something changed drastically. Suddenly firms started paying out more than half of their profits as dividends or for share-buybacks. Net capital expenditure was now mostly, or even entirely, financed through borrowing. This trend subsided in the 1990s, but came back with a vengeance in the 2000s. It reached an apogee just before the financial crisis when firms were giving back half as much money again to shareholders through dividends and share buybacks as they generated in profits.

The financial crisis precipitated a sudden reversal in that trend, as the credit crunch forced firms to de-leverage. Then the Federal Reserve stepped in, cut interest rates and pumped liquidity back into the system. Purchases of Treasuries and mortgages under the quantitative easing programme squeezed out traditional holders of those assets, pushing them into the next best thing: investment grade credit. So corporates suddenly found it easy and incredibly cheap to borrow again. Sure enough, the old ways have returned and the entire sum of corporate profits is once again being re-routed into dividends and share buy-backs (chart 2).

Yet the increase in leverage has nonetheless been smaller (relative to profits) than before the crisis. What had to give for firms to achieve the same payout ratios to shareholders? Unfortunately for any investor with more than a short-term investment horizon, firms chose to cut back on capex. Since capex is the source of growth for firms, this near term gain comes at the cost of longer term growth.

The economist Stephen E Landsburg famously summarised economics this way: "People respond to incentives. Everything else is commentary." All this corporate behaviour can be explained by incentives. So here comes the commentary: the incentives faced by those who run firms in the US encourage them not only to favour debt financing over equity financing, but also encourages them to favour increases in share prices over the long-run expansion of the business.

Corporate CEOs often have a lot of their compensation paid in shares. This is meant to align the incentives of the CEO with those of the shareholders, since the CEO becomes a shareholder. And to an extent it does, or at least to some of the shareholders. There are very different types of shareholders: the short-term investor who turns over their shares in a matter of days or months, and the long-term investor who holds the shares for many years or decades (such as pension funds). With an average tenure of a bit under a decade, you might at first think CEO incentives were more aligned with the longer-term investors.

But that ignores the risk side. If the share price does badly, perhaps because the CEO favours investment when competitors favour dividends or share buybacks, there is a risk that the CEO could lose their job. So the CEO has an incentive to ensure that the share price is high because he or she does not know when they may lose their job. Also, a CEO is more likely to be offered a lucrative job elsewhere if their existing share price has risen.

The second big incentive is a flaw in the tax system. Interest payments on debt count as an expense against tax, but dividends paid out on equity do not. In other words, it is cheaper to raise funds through debt issuance than equity issuance. Simply borrowing money to buy back shares can improve cash flow thanks to the tax saving. When interest rates are ultra-low, the incentive to boost the share price through buybacks is even higher.

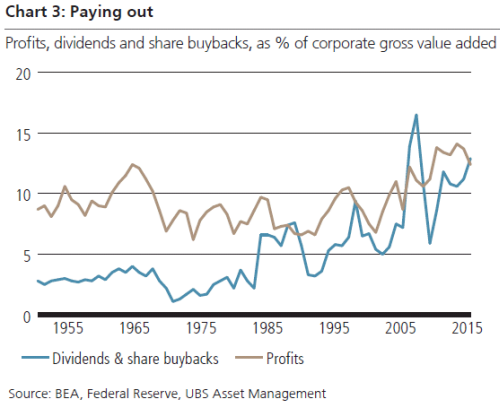

No surprise then that profit margins have been rising (at the expense of capital expenditure) relative to gross value added of non-financial corporates (this is the 'GDP' of business) (chart 3). The upward trend in profits actually masks the increase in dividends and share buybacks in the charts above. Dividends and share buybacks have risen drastically relative to profits.

Aside from the obvious questions this raises about corporate governance, there are broader questions. If firms have an incentive to divert cash from new capital investment towards profits, potential growth suffers. That matters for the Federal Reserve: the lower potential growth is, the lower the threshold of growth at which spare capacity disappears – and the sooner you get inflation. Higher interest rates would hurt firms who borrowed a lot to buy back shares. Perhaps that is the punishment for avarice?

Der komplette Marktkommentar als PDF-Dokument.

Diesen Beitrag teilen: