UBS: Inventive story

Recent weakness in the US is largely down to an inventory adjustment, but this recent move just highlights the long rebuilding of inventories relative to sales since the financial crisis. Does this reflect a conscious decision to hold higher inventories, or is it a sign of continually disappointing sales?

25.11.2015 | 14:12 Uhr

Possibly the biggest single explanation of why growth has been less volatile since the mid-1980s can be expressed in three words: "just-in-time". With the advent of modern communications, transport and computing, firms became much better at handling inventories, getting their raw materials and finished goods "just-in-time" for when they needed to be used or sold. Prior to this change, firms often held large stocks of goods on hand. When a recession came, they would just run down those inventories. This effectively meant no new orders for those further along the supply chain, so those firms effectively shut down during the recession. Then when demand picked up, they would rush to get inventories back up. So that meant bigger swings down and bigger bounces back up.

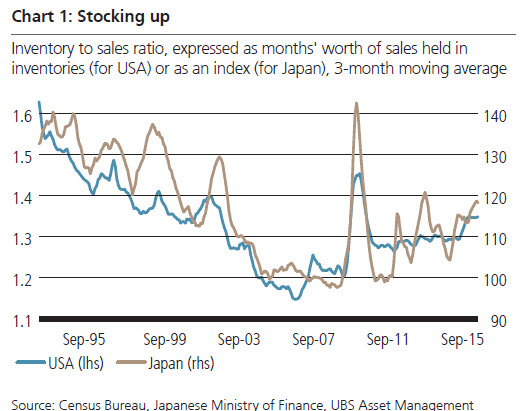

In the modern world, just-in-time processing and inventory management means that firms run lean. Between 1992 and 2005 the average ratio of inventories to sales in the US fell from over 1.6 months' worth of sales, down to almost 1.1 months' worth by 2005 (chart 1). This may not sound like much, but in 2005 that difference was equivalent to USD 200 billion. Since then, however, the ratio has been rising, and is now back up to the levels of the late 1990s. The spike in 2008 was the collapse in sales that came from recession, but the increase started before that and has continued ever since. And it is not just the US: although more volatile, the Japanese index has followed the same pattern.

Some recent events may have encouraged a higher level of inventories. The Great Japan Earthquake of 2011 led to a sudden disruption of Japanese industrial production, which gave rise to wide, and sometimes surprising, disruptions to the fragile supply chain. But perhaps most importantly, near zero deposit rates make the opportunity cost of holding onto inventories much lower: inventories are effectively inflation-linked - as the selling price of the goods in your inventories goes up, so does the value of your inventories. So the real return on inventories is probably higher than the returns firms can achieve by depositing the cash in a bank.

The Great Recession also disrupted supply chains. Producers were often unable to secure commercial paper to finance short term expenditure, making it hard to identify. Paradoxically, the impact of this was muted because everyone wanted to run down their inventories as quickly as possible, so an inability to replenish inventories was not really a problem. But the experience revealed to firms just how fragile their supply chain was, and that perhaps the inventory to sales ratio was too low by 2006. In investment terms, firms had been maximising returns by reducing inventories, but in so doing were taking too much risk. A higher level of inventories may be the new norm for business, although this may edge down slightly as interest rates rise.

Diesen Beitrag teilen: