Schroders: Turbulent times in technology

James Gautrey looks at why and how the IT world has changed in recent years and whether valuations have sufficiently improved to revisit the sector.

22.07.2014 | 13:52 Uhr

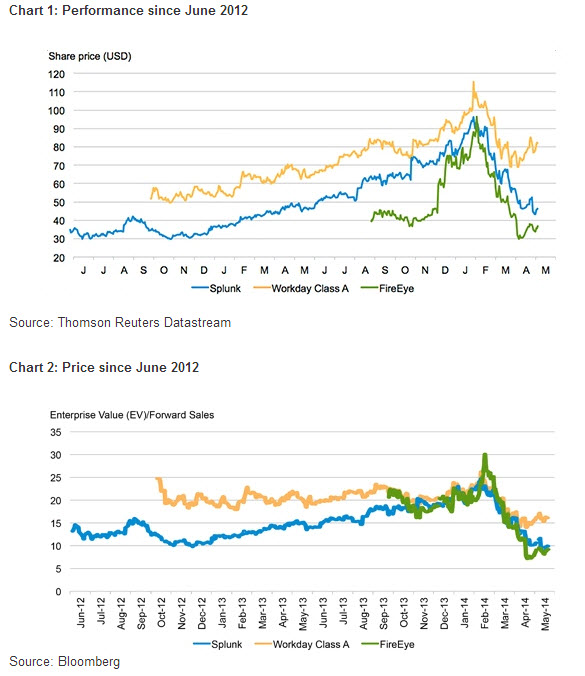

In the halcyon days of 2013, disruptive technology firms pioneering a generational change in information technology (IT) were the place to be. The poster child stocks of Workday, FireEye and Splunk epitomised the fast-moving innovators and investors were happy to pay huge multiples just to own a slice of them (see chart 2). Revenue growth was the only focus; profitability was often seen as a sign of weakness – a reflection of inadequate growth opportunities or spineless management!

The rally continued until March 2014 when, to paraphrase US economist and ex-Federal Reserve chairman, Alan Greenspan, the ‘punchbowl’ was taken away. Bond yields started falling and expensive growth stocks were punished. Perhaps investors began to wonder why they owned anything which they themselves categorised as expensive.

This article therefore seeks to define more clearly the fundamental changes in IT that drove this rally and asks whether valuations are now interesting enough to look again. In summary, we find the sector’s aggregate valuations still stretched but see pockets of opportunity for stockpicking among underappreciated names that are likely to benefit from the disruptive changes across the sector.

The changing face of ITThe consumption of IT by both consumers and corporates is undergoing a seismic shift such that existing architectures are either unable to cope or not fit for purpose. Consumer data demand, both on fixed and mobile devices, is insatiable. Photos are shared on Facebook, videos watched on YouTube and movies downloaded from Netflix. Combined, these services represent gigabytes of data consumption which need to be delivered in near real-time to a plethora of different devices. Ten years ago, none of this really existed. Mobile traffic has grown almost 100 times since the birth of the smartphone era in 2008 and Cisco, the global network developer, believes it is set to triple again by 2018. Netflix has just 1.5 million subscribers in the UK but the company now accounts for 20% of peak internet traffic. At current levels, if just one in three UK households were to sign up, UK bandwidth would be exhausted simply streaming the popular television series Breaking Bad and House of Cards!

On the corporate side, innovation is being driven by three phenomena. Firstly, the consumer-facing companies trying to deliver extraordinary amounts of data in real-time (such Google, Facebook, Amazon, Netflix etc) have been forced to change. Traditional IT architecture was too expensive and could not perform as required. So these companies decided to build their own systems known as the Software Defined Data Centre. This essentially allows owners to deploy computing (network, storage, processor) resources as and when required without traditional limitations of location, implementation time and cost. At its heart, this change involves replacing proprietary systems with a controlling software layer and commodity physical hardware. Facebook saved 35% on server costs alone in the first year it implemented these changes.

Secondly, corporates are increasingly interested in gathering and analysing vast amounts of data in real-time, which is generally referred to as ‘big data’. This is being enabled by new analytical software platforms, database technology and, importantly, a shift from disk-based to memory-based systems. This essentially involves storing data on DRAM (dynamic random access memory) chips within the computer rather than on external hard disks and is known as ‘in-memory’ technology and has huge benefits in areas such as processing speed, energy usage and physical saving of space.

Lastly, enterprise and consumer software is increasingly moving to ‘cloud’ computing whereby data is stored externally and accessed via the internet. The advantages are numerous and include reduced costs, multiple device integration and easy deployment. It seems likely that most software will be delivered this way in the next 10 to 20 years. Enterprises will probably use a hybrid approach in which they use a combination of public and private data centres in order to meet performance requirements and allay security fears.

Concerns about security and data loss are often cited as a key reason why enterprises will be uncomfortable moving to the cloud. Interestingly, Workday, a leading cloud company, have reportedly had no security breaches in their data-centres since founding in 2005. Clients often realise on closer inspection that the security in place in a cloud specialist’s data centre is often superior to their own so worries about data loss will likely subside with time and the move to the cloud will gather steam.

All of these changes are evident in most of our homes and working environments. They will most likely continue unabated in both developed and emerging markets, forcing IT metamorphosis in every corner. From an investment perspective, the challenge is to figure out what this all means for those companies involved, both incumbents and innovators and, from that, the impact of innovation on earnings growth and ultimately valuations.

Are valuations interesting again? In technology investing, the most popular trains of thought are that valuation doesn’t matter for compelling stories and that value investing doesn’t work because stocks are cheap for good reason. Neither is correct and indeed both stem from the same issue that in an industry so prone to change, investors allow their emotions to forecast whatever is needed to justify their beliefs.

Over the last two years, positive sentiment about the growth potential afforded by innovation in the sector pushed innovators’ valuations to eye-watering levels while incumbents were largely considered ‘yesterday’s men’. While this has corrected somewhat since March 2014, innovators’ valuations still do not offer a compelling risk / reward proposition in our opinion. They fail to recognise that in a world where profits do not matter, disruption is easier and hence competition higher. Today’s dinosaurs were the disruptors of the late 1990s and there is little reason why this pattern would not continue. Incumbent technology giants are also reacting to the changing environment and their resources should not be underestimated. This means that for many innovative companies, the long-term confidence required to justify current valuations is simply not reasonable.

Diesen Beitrag teilen: