NN IP: Global growth is holding up well

Global growth is holding up well, but trade risks are rising. Vigilance is required on the effect of those risks on confidence and the real economy.

20.08.2018 | 16:05 Uhr

The big story so far in 2018 is that the year started with a soft patch that followed very strong growth momentum in late 2017. To some extent the soft patch may have been payback from that strength. What’s more, in Q1 there were all kinds of idiosyncratic factors at play that weighed on growth, such as abnormal weather patterns, strikes, a later pay-out of US tax rebates etc. In this respect, it was reassuring to see a strong rebound in global consumer spending in Q2 while high frequency indicators of investment spending also improved somewhat in the face of continued robust profit growth rates and strong capex intentions surveys. The feed-through into data on global industrial production remained limited, however, as this sector was facing an inventory correction which acted as a drag on production growth. This observation is important because a disproportionate share of the data we track (and which feed into surprise indices and economic momentum indicators) pertain to the industrial sector. The simple reason for this is that activity is much easier to measure in that sector than in the service sector. As far as we can see, the latter held up very well throughout the first half of this year, which is probably why various international institutions continue to forecast robust global growth both this year and next (albeit with downside trade risks). In a way, markets have been contemplating the balance of these improved data since the start of Q2 and rising trade risks. These elements pull the distribution of future economic outcomes in opposite directions. As a result, it is no surprise that asset markets have been pretty volatile and that some asset classes (equities) have been relatively directionless over the past few months.

The same can be said for economic momentum indicators. Surprise indicators have understandably been heavily influenced by the soft patch in the global industrial sector as well as the fact that business and consumer confidence indicators have reached very high levels. This makes the room for further rises much more limited while the growth surge in Q4’17 had kept expectations of these confidence readings at elevated levels. As far as economic momentum indicators are concerned, one can distinguish between indicators that try to gauge the growth level and indicators that try to capture the marginal change. It is tempting to assume that the latter could be more relevant for markets which, after all, trade mostly on the marginal news flow. To a first approximation this is probably true, but perhaps we need to nuance this argument just a bit. In reality, markets trade on shifts in the perceived distribution of future economic outcomes. The implicit assumption here is that all risks can be quantified, which is not the case in the real world. Black swans or unknown unknowns will always be there to haunt the minds of investors. In this sense all economic momentum indicators are imperfect, which means it makes sense to diversify and look at the information from as broad a set of indicators as possible.

What’s more, at the current juncture one can make a case that level indicators can be used to qualify one’s judgement about change indicators. After all, in the consolidation phase the trend in level indicators will be mostly sideways but there will always be some volatility. This volatility will be picked up by the change indictors, which may therefore, at face value, give the false impression of a bearish shift in the distribution of future economic outcomes. On the other hand, an increase in trade risks which starts to feed into more cautious behaviour by the corporate sector will first show up in sentiment indicators. If and when this happens, change indicators will pick this up. Hence, it is very difficult to distinguish between normal volatility and a genuine change in sentiment, especially in the consolidation phase.

Genuine versus false declines in momentum indicators

The question is then whether or not we can say something more to try to distinguish between “genuine” and “false” declines in economic momentum indicators. After all, we know that trade risks are rising and there may well already be some impact. A useful strategy here would therefore be to focus mostly on the forward looking/expectations components of the surveys, especially in the manufacturing sector and in regions most exposed to trade (Europe, Japan, Asia). In addition to this, we should track capex intentions as well as high frequency data on capex. The evidence here is a bit mixed. The global manufacturing PMI contains a future output index which is not used in the headline calculation. This index has decreased substantially over the past few months and is back at levels last seen during the 2014/16 disinflationary dollar/oil shock. Nevertheless, the future output index did stabilise in July and the decline over the past few months is also likely to have been a reflection of the underperformance of global industrial production relative to global GDP. Meanwhile, the momentum in US durable goods orders and shipments remains reasonable while there have been some disappointments in Germany and Japan. Still, it is unclear to what extent this divergence is driven by the US fiscal sugar high and the associated boost to consumer spending. Zooming in on the export-sensitive parts of the world we see that capital goods export expectations in the German IFO survey have declined over the past few months. This holds even more strongly for auto sector export expectations. The latter in particular can be attributed to the threat of US tariffs on European cars (which seems to have been averted for now). Incidentally we see a similar decline in auto sector expectations in the Reuters Tankan Survey in Japan. On top of this we see some weakness in Asia ex-China exports and industrial production but it is unclear to what degree this relates to trade worries or to the inventory adjustment in the global industrial sector.

With respect to capex intentions, in Germany the latest IFO investment survey still shows pretty robust capex intentions for the fall of 2018. More generally in Europe, lending standards for corporates continue to ease and credit demand continues to be strong. Meanwhile, our own index for the US shows a very small rebound and remains at a high level. This corresponds with some interesting findings from a recently created Atlanta Fed survey which concludes: “About one-fifth of firms in the July 2018 SBU say they are reassessing capital expenditure plans in light of tariff worries. Among this one-fifth, firms have reassessed an average 60 percent of capital expenditures previously planned for 2018–19. The main form of reassessment thus far is to place previously planned capital expenditures under review. Only 6 percent of the firms in our full sample report cutting or deferring previously planned capital expenditures in reaction to tariff worries. These findings suggest that tariff worries have had only a small negative effect on U.S. business investment to date.”

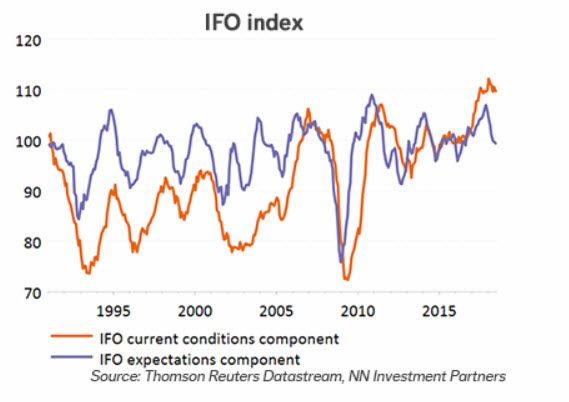

All in all, we may well see some influence on (the expectations component of) business confidence metrics but so far this seems to be confined to sectors directly exposed to trade risks. To the extent that we see a general decline in expectations components this may also be the result of business confidence coming off the boil a bit after a very strong H2’17, especially in the manufacturing sector. Moreover, while very useful as an indicator of animal spirits, expectations components do not always translate into reality. The history of the German IFO index can be instructive in this respect.

The expectations component of the IFO index seems to lead current conditions a bit and in general, the two move pretty closely together. However, there are exceptions and one such occurrence started in the spring of 2002 when expectations surged ahead while current conditions failed to pick up. This was a period in which the euro started to appreciate substantially and various accounting scandals came to light. Expectations then retraced and subsequently rose again, which correctly anticipated a rise in current conditions. Nevertheless, throughout 2004-07 expectations were fairy volatile in the face of steadily rising current conditions and very decent global and EMU growth rates. Since 2007 current conditions have generally been at a higher level than in the 1994-2005 period, with the exception of a steep fall in 2008/09 from which the index quickly recovered. This can be explained as a result of the German reunification and subsequent structural reform. The reunification led to a significant deterioration in the competitiveness of German industry, which only started to recover after far-reaching labour market reforms in 2004. Since then German competitiveness has been very good and has resulted in a substantial current account surplus. The recent decline in the IFO expectations index does not look out of line with the volatility observed during the long expansion of the 1990s or the expansion of the early 2000s. As such, it could be a signal of a deterioration of current conditions, but this is far from certain.

Trade risks are rising, no evidence of significant impact yet

The upshot of all this is that we should be on guard with respect to the effect of trade risks on confidence and the real economy, but so far there is no evidence of a significant detrimental effect. One reassuring sign is that over the past month or so the consolidation phase seems to have become somewhat more firmly cemented. This is reflected in global retail sales, which rebounded strongly in Q2 while global capex seems to be settling at a decent rate that is somewhat lower than the very strong growth rates seen in H2’17. When looking at the most widely used bellwether of global momentum, the global PMI, we can say that on a trend basis it has been moving sideways since early 2017 and that the surge late last year was more or less the exception. The services PMI has been the beacon of stability in the past six months while the manufacturing PMI has underperformed. Still, the good news in that respect is that the decline in the finished goods inventory index suggests that the drag from inventories may be coming to an end. To the extent that this is true we should see a marked improvement in industrial output in the second half of this year, provided of course that trade risks do not become dominant.

Diesen Beitrag teilen: